(The score for Gay Guerrilla by Julius Eastman)

welcome to issue #21 of “tusk is better than rumours,” a newsletter featuring primers and album rankings of experimental and ‘outsider’ musicians. artist primers are published every other monday, and on off-weeks i publish a variety of articles ranging from label and genre primers to interviews to guest writers.

this week i’m excited to present a piece by dr. eva moreda rodríguez on experimental and avant-garde notation. moreda rodríguez is a musicologist who focuses on the history of spanish music from the late 19th century to today. she has published two books on music and music criticism in francoist spain, Music and Exile in Francoist Spain (ashgate 2015) and Music Criticism and Music Critics in Early Francoist Spain (oxford university press 2017). she is also an accomplished novelist. i became aware of her, however, from her great twitter account, “musical notation is beautiful,” so i asked her to write about a few examples of creative and difficult scores. her selections will be of interest to “tusk is better” readers, as they include luminaries like cornelius cardew, anthony braxton, and julius eastman.

then at the end of the issue, i have an announcement about my plans for “tusk is better” in light of the ongoing protests of police brutality on black and brown people around the country.

sign up to receive the newsletter if you haven’t already, follow us on twitter @tuskisbetter, and tell a friend. you can also reply to these emails or write to tuskisbetter@gmail.com.

Experimental and avant-garde notation: what is a score for?

For a few years I taught a two-lecture series on notation in an “Introduction to Music Studies” class for first-year students. I remember that the bit on the notation of experimental and avant-garde music always resulted in the most passionate and interesting discussions. “Is this notation?,” I would ask students while projecting one of George Brecht’s “Event scores” on the screen (or, alternatively, Steve Reich’s Pendulum Music or Yoko Ono’s Voice Piece for Soprano) – snippets of text, sometimes written in a quizzical way, instructing the performers to do various things. “Is this a score?,” I would ask again when projecting Roman Haubenstock-Ramati’s Alone (or Brian Eno’s better-known Music for Airports) – which one would be forgiven to mistake for a piece of non-figurative art.

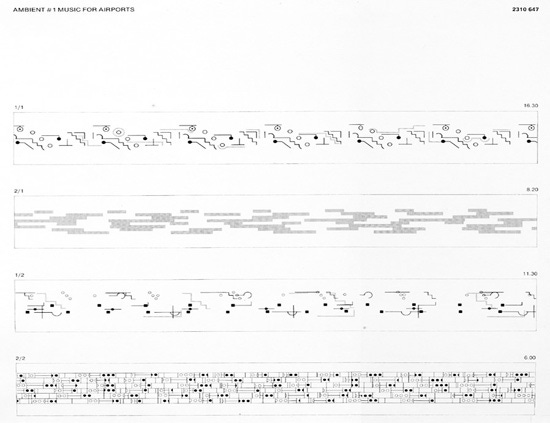

(Brian Eno’s notation for the four parts of Music for Airports, from the album sleeve)

My students – like most of us schooled in the classical tradition – were bemused to be presented with scores without clear indications of what notes to play, how long to play them for or how to fit them into a rhythm. Yet, after discussion, we tended to find some ways in which these examples resembled aspects of other forms of notation we knew from earlier eras. Brecht, Reich and Ono, for example, in their own way, provide a set of instructions for performers – not unlike lute tablatures, which told you which fret you should put your finger on, but not which pitch you needed to play. As for Haubenstock-Ramati’s and Eno’s graphic scores, they act as a powerful reminder that, across the centuries, traditional notation was not always simply functional, but it often included too a significant visual component – for example, in the work of the late medieval composers collectively known as Ars Subtilior; here, scores were sometimes drawn in playful shapes, such as a harp or a heart.

In these discussions with my students, we found in the music of the past a gateway that helped us make sense of some of the wildly imaginative, innovative and puzzling notations composers and performers started to experiment with from the 1950s onward. However, we should not underestimate the extent to which these experiments intended to break away from established forms of notation that composers were increasingly seeing as insufficient to pursue their creative vision. Over the course of several centuries, Western art music notation developed to be very good at giving precise indications of pitch and rhythm, but it remained more vague concerning other key elements of music such as timbre or the performer’s contribution to materializing the piece. But – my students and I always ended up asking ourselves - what does a piece with no set pitch or rhythm “sound” like? And – perhaps equally importantly – what does it look like?

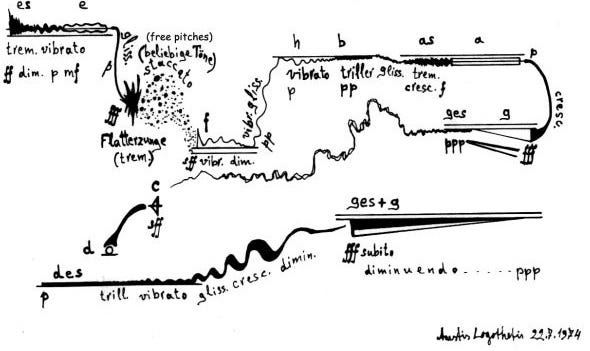

In exploring these questions, some composers took a relatively controlled approach – such as Anestis Logothetis, a Greek composer who developed most of his career in Austria from the 1950s onwards, with connections to the Darmstadt music courses, the electronic studio of West German Radio (WDR), John Cage and other key names of the nascent avant-garde musical scene. Logothetis’ graphic scores consist of a number of discrete elements, to each of which is attributed a meaning by the composer – for example, whether pitch should be high or low; which dynamics should be implemented; whether the sound should have any specific timbral quality or use an extended technique. Still, performers, in interpreting the combination of signs that constituted the score, would have a considerable degree of freedom in choosing which exact pitches to play, for how long to stay in a certain range or timbre, or how to respond to each other.

(An example of how Anestis Logothetis’s discrete symbols combine in a score)

“But then, doesn’t this mean that you can play whatever?” That’s another of the questions my students would often ask in these debates on notation. Yes and no – in fact, one of the reasons why composers were attracted to these kinds of notations was that they gave increased agency to performers in the shaping of the piece and that they opened up avenues for collaboration and co-creating, rather than the performer simply sticking to the pitches and note values on the page. Consider, for example, Cornelius Cardew’s Treatise – a 193-page score composed of shapes and symbols; at the bottom of each page, a five-line staff runs throughout the entire work, as if to remind us silently that this is music and not some kind of visual art experiment. Unlike Logothetis, Cardew – a British native who then renounced the avant-garde in favor of more politically committed forms of music - did not give any precise instructions to performers or drew up a code to decipher his score. He did not even indicate how many performers or which instruments should be included, or how long the piece should last. However, Treatise is not a “free for all,” and Cardew expected performers to agree beforehand on how signs should be interpreted in performance. Logically, this has resulted in wildly different interpretations (“realizations”) of the score. Questions that me and my students explored together inspired by Cardew’s score included: in what sense can we regard these as performances of the same work, given that we wouldn’t be able to identify them as such if we didn’t know all of them had resulted from the same score? And how does this redefine the role of composers and performers in co-creating a piece of music?

Cardew only went as far as printing a running five-line staff on the bottom of each page of the score to remind us that this is a score to be performed. Other composers, however, kept some elements of traditional music notation in their scores while exploring ways to make them more open and less deterministic – such as American composer and multi-instrumentalist Anthony Braxton, who worked mostly in the domain of free jazz (indeed, another question that these scores pose is how stable is the boundary between classical music and other genres where improvisation was more firmly established). Like Logothetis, Braxton devised specific signs to denote certain effects or timbres (what he called “sound classifications”), including “smooth sounds”, “soft sounds”, “smeared sounds” and “sound beam.” These, again, require considerable critical insight and involvement from performers in order for them to be fully realized. Some of Braxton’s scores rely solely on such signs; others, instead, combine them with short snippets of musical notation. Performers are to base their improvisations on these notated short passages, while at the same time getting guidance from the signs and shapes surrounding them. For example, in Composition #76 Braxton uses colors to indicate mood, and shades of colors to indicate tempo and dynamics.

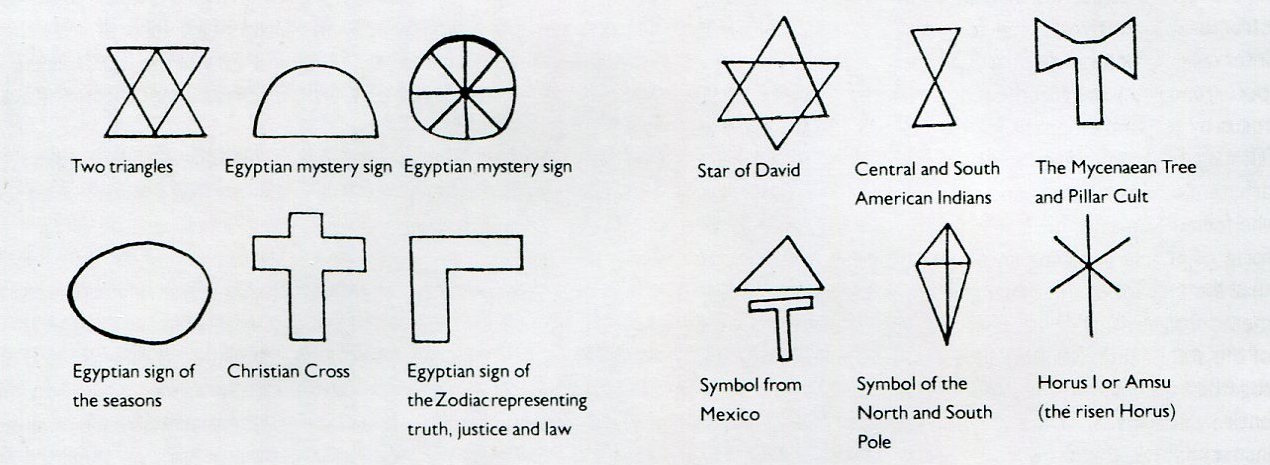

(Symbols from Anthony Braxton’s Composition #96)

Composition #96, on the other hand, superimposes an orchestral score in conventional notation with a visual score consisting of religious symbols, such as the Christian cross and the star of David. These signs are not intended for the musicians, though, but for a photographer: she should, in advance of the performance, scout her environment in search of manifestations of these symbols in the natural world and photograph them; the photographs should then be synchronized with the performance of the orchestral score. Braxton’s use of photography, incidentally, is an excellent example of how these graphic scores are often difficult to separate from the visual arts. Indeed, there are several other examples of creators who moved between one and the other seamlessly, questioning even the notion that a boundary existed between the two. Juan Hidalgo, who introduced John Cage’s oeuvre and thinking in Spain, was active as both a composer and visual artist. German conceptual artist Hanne Darboven worked for a long time on her “Mathematical Music” pieces: these consist of rows and columns of numbers, which can also be performed as actual pieces of music.

Composer, singer and overall genius Julius Eastman, on the other hand, stuck to recognizable signs from traditional music notation in some of his best-known pieces, such as Gay Guerrilla. On a conventional five-line staff, pitches are clearly given but note values and time signatures are not: most notes appear only as black heads, the same pitch repeated again and again eight or thirteen or twenty times in a row. Eastman offers some written guidance as to how to interpret the spread of notes on the page (“play once on cue,” “chords go together”), as well as timings; however, performers still need to agree on a considerable number of aspects of the performance – how many performers will play, what instruments will they play, at what speed and dynamics. Interestingly, however, as Jeff Weston has pointed out, this freedom has not always been fully realized by performers: instead, home recordings of the pieces made or supervised by Eastman have often been used as the model from which new performances are crafted. Which leads to a new question, one more that my students and I explored without ever getting to a final answer: Can such recordings then act as a new score to be respected at all costs?

-Eva Moreda Rodríguez

i wanted to give dr. moreda rodríguez’s piece its proper space, as it’s been in the works for some time and i find it illuminating as a non-academic, non-performing listener of the music she covers. however, i also want to use this week’s issue to address the role of music writing at a time when its importance pales in comparison to the wrongs being protested in the streets every day. the mundane run of album reviews and profiles can seem like a needless distraction from the urgent work of achieving justice for george floyd, breonna taylor, ahmaud arbery, tony mcdade, and countless others.

i do think that music writing has a role to play today. it can alert us to the long history of police violence and oppression in response to black music, from miles davis’s beating at the hands of the nypd to the unnecessary clampdown on the brooklyn drill scene. it can draw attention to ways of supporting black musicians, as in the wave of funds redirected on this last bandcamp day or the recent crowdfunding for house legend adonis. and it can remind us that so much black music is already protest music, even if this history has been obscured by its subsequent appropriation by white audiences.

that being said, i don’t feel that my musings on which is the best jim o’rourke album are what’s needed at this time. so for the next several weeks, i’m going to use the (small) platform i have through the newsletter to direct attention to black music critics. in each issue, instead of my own writing, i will link to several pieces from emerging voices and established writers alike. i’ll be glad if i can get a couple of hundred new pairs of eyes on the work of those most disadvantaged by the systemic racism of the music journalism industry, and hopefully you all will find a new writer or two to follow in the coming weeks.

at the bottom of each issue i’ll also include a link to donate to a mutual aid fund, bail fund, or other community-focused cause. let’s start now with the logan square mutual aid fund in chicago. send a few dollars their way if you can or, if you are in the chicago area, consider donating your time!

stay safe, stay strong, mask up, keep fighting.

and as always,