guest writer: marshall gu on philip glass

"After the premiere of 'Einstein' in 1976, Glass was asked questions like 'How dare you do this?' and 'What was that supposed to be?'"

(photo by steve pyke)

welcome to issue #15 of “tusk is better than rumours,” a newsletter featuring primers and album rankings of experimental and ‘outsider’ musicians. artist primers are published every other monday, and on off-weeks i publish a variety of articles ranging from label and genre primers to interviews to guest writers.

this week we have our first guest writer, marshall gu, writing about the great minimalist composer philip glass. gu has written for popmatters, pretty much amazing, and tone glow. here, he walks us through ten of the most notable glass recordings from throughout his career.

sign up to receive the newsletter if you haven’t already! and follow us on twitter @tuskisbetter! and tell a friend! also you can reply to these emails or write to tuskisbetter@gmail.com.

Minimalism is exactly what it sounds like: music stripped down to its essentials. Work from its most prominent voices, like Philip Glass, Steve Reich, La Monte Young and Terry Riley, prominently features repeating patterns that change very slightly over time. If one of the barriers to classical music was its complexity, then minimalism lowered this barrier by chipping away at the music until you were left with an implied beat in the music’s steady pulse. Grooves for us introverts! Their approach has also influenced non-classical music. Notably, the Velvet Underground came out of an adjacent 1960s New York scene and applied minimalist ideas to their proto-punk music, while Captain Beefheart quoted Steve Reich and the Who name-dropped Terry Riley. Minimalism’s guiding principles would be picked up by electronic and hip-hop musicians decades later, from the Orb to Aphex Twin and even to trap rap.

All four of these artists are easily distinguishable, despite their similar approaches. Philip Glass can be recognized because he creates dark, even cynical, moods. Because he was influenced by jazz artists like John Coltrane and Lennie Tristano more than someone like Riley was, his work could never—and wouldn’t aspire to—achieve the happy-go-lucky optimism of a piece like Rainbow in Curved Air. There are very, very few Philip Glass songs that can be described as ‘happy.’

Born in Baltimore on January 31, 1936, Philip Glass developed an early appreciation for music because his father owned a record store. He eventually moved to Paris in the early ‘60s to study composition under Nadia Boulanger. It was also in Paris where he first worked with Ravi Shankar, and the teachings from both would have a profound effect on his own compositions. In 1967, Philip Glass moved to New York City, where he was introduced to minimalism while attending a performance by Reich, which informed some of his early compositions. He writes in his memoir Words Without Music that:

I began to use process instead of “story,” and the process was based on repetition and change. This made the language easier to understand, because the listener would have time to contemplate it at the same time as it was moving so quickly. It was a way of paying attention to the music, rather than to the story the music might be telling. In Steve Reich’s early pieces, he did this with “phasing,” and I did it with additive structure. In this case, when process replaced narrative, the technique of repetition became the basis of the language. (220-221)

Still active to this day, Glass has developed an extensive catalog. Rather than delve into each of his releases, we will go chronologically through ten of his most notable albums, good or bad. A point of housekeeping: the year refers to the album’s release date and not the year the work was composed.

Einstein on the Beach (1978): This is the magnum opus, the one that will either scare you away or make you turn it up loud to scare your parents. Sure, you’re listening to classical music—but really edgy classical music. Much of the attention paid to this piece is on account of how over the top it is; in his autobiography Words Without Music, Glass noted that after the premiere of Einstein in the Avignon Festival in France in 1976, he was asked questions like “How dare you do this?” and “What was that supposed to be?” Einstein on the Beach is framed as an opera because it has the superficial characteristics of an opera, including traditional voice types and recurring motifs. But it doesn’t actually play like an opera. What does it play like? It plays like any rock album produced by Brian Eno that builds to a critical mass, like his work with Talking Heads or U2 around this time. In Words Without Music, Glass notes, “In classical music, there are allegros and prestos in all kinds of pieces, but they were usually presented as contrast to other parts. There would be slow music, then fast music. I have done that myself many times, in string quartets. But with Einstein, the idea of an unstoppable energy was all there was. There was no need for a slow movement” (289). That Einstein sold out at the Metropolitan Opera House for two nights but Glass still had to go back to odd jobs like driving a cab was two lessons at once: (1) even successful art doesn’t pay as much as it should, and (2) New York ain’t cheap, even in the 70s.

Glassworks (1982): The best starting point into Glass’s aesthetic because it presents six, bite-sized chunks across forty minutes instead of one long piece. Glassworks was his first album under CBS (Sony Classical), who insisted on shorter pieces. If Glass’s general aesthetic consisted in stripping music down, then Glassworks represents a step further in that direction. Even though these are composed as individual songs, that the bookends are titled “Opening” and “Closing” while the second and penultimate tracks both feature heady rushes of synth means it’s still meant to be played as an album. Each individual song is hypnotic in its own way--“Opening,” with its triplets over duplets, naturally evokes rain while looking ahead to “Solo Piano” in its meditative tempo and dynamic--but ultimately they are less hypnotic than Glass’s long-form compositions.

Koyaanisqatsi (1983): Comic book nerds, myself included, will recognize some of these pieces because Zach Snyder used them in Watchmen. So thank you, Snyder, for doing something right. Koyaaniqatsi is the soundtrack for Godfrey Reggio’s film of the same name, and it works fine outside of the context of his time-lapsed footage of cities and the people that inhabit them. Like Glassworks, Koyaanisqatsi comprises six relatively short pieces that span only 46 minutes, about half the length of the film. In 1998, Glass re-recorded a longer version and labeled it a proper album rather than a soundtrack. Rather than a somewhat palindromic structure, Koyaaniqatsi builds crescendo upon crescendo. These are some of his best build-ups in short form.

The Photographer (1983): Also released in 1983 and thus overshadowed by Koyaaniqatsi, The Photographer might not be one of Glass’s most recognized pieces, but it deserves to be. This is a mini-opera based on the life of the English pioneer of photography Eadweard Muybridge. Muybridge’s work, which is like looking at individual cells of a film reel, each image slightly different than the last, is a visual analog to Glass’s music. Of note in this piece are the twinkling piano line and the ethereal vocals from Dora Ohrenstein on opener “A Gentleman’s Honor.” Similarly, Paul Zukofsky’s violin lines make “Act II” stand out among Glass’s similarly orchestrated compositions of this era.

Akhnaten (1987): After Einstein, Glass wrote a more traditional opera in Satyagraha in 1979, and then completed his “Portrait Trilogy” with Akhnaten: three operas about famous historical figures representing, respectively, science, politics and now religion. Akhnaten is particularly notable because when the orchestra pit where it premiered was not big enough for the performers, Glass made the impulse decision to remove all the violins. From Words Without Music: “Without the violins, half the orchestra was gone. What was left was a very different orchestra in which the highest string instrument was the violas. The violas became the firsts, the cellos became the seconds, and the double basses became the cellos. Now the orchestration was very dark and rich” (318). Of particular note is “Funeral for Amenhotep III,” which, thanks to the two drummers, sounds like Glass’s most overt rock song.

Powaqqatsi (1988): The sequel to Koyaaniqatsi, Powaqqatsi represents Philip Glass’s first incorporation of ‘world music’ into his sound, from South American children choirs to African percussion. Notably, this was after Glass worked with collaborators like David Byrne and Paul Simon on Songs From Liquid Days, both of whom helped create a market for world music. Even though some of the album’s many climaxes like “Train to Sao Paulo” and the overly-busy “CAUGHT!” don’t come off, and even though many of the tones have dated and now sound ‘cheap-exotic,’ it’s the percussion throughout that helps distinguish many of Powaqqatsi’s individual songs, especially when they contribute to the frenzy of movement and traffic on opener “Serra Pelada.” In this context, when Glass returns to the European crescendos on would-be centerpiece, “Anthem,” which is 18 minutes split up across three different tracks, it is suddenly the odd man out.

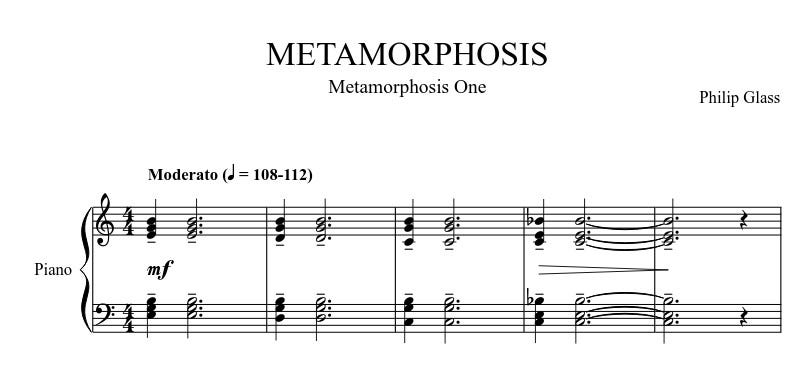

Solo Piano (1989): Though Glass had been stripping away elements from his music for over a decade, Solo Piano is his first recording for a single instrument. This album compiles three compositions, highlighting Glass’s gift for simple chords and melodies. The model for “Metamorphosis,” which takes up most of the album’s run-time, is Erik Satie. The piece recalls Satie’s quiet, somber compositions that feel like they could stretch for an eternity, especially in the lingering chords of the first movement. (The idea of minimalism can be traced back as early as Satie’s pieces like “Vexations,” which was brought to New York City in the ‘60s by John Cage, and “Méditation”). “Metamorphosis” is also constructed in an arch form like some of Steve Reich’s pieces earlier in the decade including Desert Music, while Wichita Vortex Supra was named after an Allen Ginsburg poem, with whom Glass would collaborate on Hydrogen Jukebox a few years later.

Passages (with Ravi Shankar) (1990): Philip Glass first met Ravi Shankar in the 1960s at a time when Shankar was mostly known for his friendship with George Harrison. Prior to working with Shankar, Glass set off to buy one of Shankar’s records, which bewildered him: “At my first listening I couldn’t make heads or tails of it. At twenty-nine, I was completely ignorant of any non-Western music” (130). But working with Shankar influenced how Glass approached his compositions for the rest of his career. Passages sees the two reuniting and collaborating decades later, with modern American classical music contrasted with traditional Hindustani classical music. The movements go back and forth: the first track “Offering” is based on a theme Shankar gave to Glass, “Sadhanipa” is then based on a theme Glass gave to Shankar, and so on. Ultimately, it’s Shankar’s presence that helps distinguish Passages as one of Glass’s most interesting late-period works.

Low Symphony (1993): Composed in 1992, Low Symphony is notable as his first attempt at writing a symphony. He would go on to write 11 more. This one is taken “from the music of David Bowie & Brian Eno,” with two songs from Low (“Subterraneans” and “Warszawa”), and one non-album rarity written around that time (“Some Are”). As a symphony, this one doesn’t hold up because it sounds like three individual pieces with no overarching structure. As a David Bowie tribute, it’s also not interesting because Glass was not ambitious enough to apply his methodology to Bowie’s ‘songier’ fragments on the first half of Low. A few years later, however, he would do just that, striking a balance between the songs and ambient tracks of Heroes in his fourth symphony. Glass finally completed the ‘Berlin trilogy’ in 2019 by taking on Lodger.

How Now/Strung Out (2014): Released in 2014, this compiles two of Glass’s earliest compositions, both composed in 1968. It is also the earliest recording of Glass’s compositions, so it’s fitting that we end our list at the beginning. “How Now” is a 30-minute solo organ piece that sounds nothing like how he’d approach the solo piano two decades later. There’s no sense of intimacy here—it’s a full-out attack of stabbed, staccato notes, and an exercise in patience for both the performer and the listener. “Strung Out,” performed by Dorothy Pixley-Rothschild, is sweeter, and not just because it’s almost half the length. Not essential to his legacy, but fascinating to hear nonetheless because of how much he would improve compositionally. It’s worth noting Steve Reich and Terry Riley’s influence on these early pieces, as they both put out some of their most influential pieces in the ‘60s while Philip Glass was only just getting started.

-Marshall Gu

you can help support the newsletter for the price of a coffee. all donations go toward paying guest writers and offsetting the costs of production (bandcamp downloads, food, stimulants)